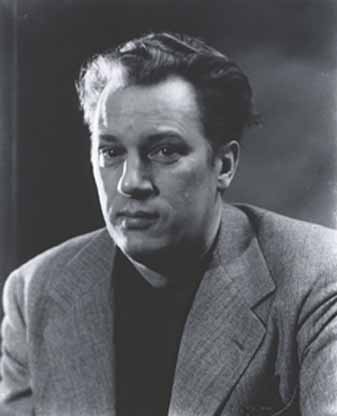

BYRON BROWNE

1907-1961 Byron Browne was a central figure in many of the artistic and political groups that flourished during the 1930s. He was an early member of the Artists’ Union, a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, and participated in the Artists’ Congress until 1940 when political infighting prompted Browne and others to form the break-away Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Browne’s artistic training followed traditional lines. From 1925 to 1928, he studied at the National Academy of Design, where in his last year he won the prestigious Third Hallgarten Prize for a still-life composition. Yet before finishing his studies, Browne discovered the newly established Gallery of Living Art. There and through his friends John Graham and Arshile Gorky, he became fascinated with Picasso, Braque, Miró, and other modern masters.

Byron Browne was a central figure in many of the artistic and political groups that flourished during the 1930s. He was an early member of the Artists’ Union, a founding member of the American Abstract Artists, and participated in the Artists’ Congress until 1940 when political infighting prompted Browne and others to form the break-away Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors. Browne’s artistic training followed traditional lines. From 1925 to 1928, he studied at the National Academy of Design, where in his last year he won the prestigious Third Hallgarten Prize for a still-life composition. Yet before finishing his studies, Browne discovered the newly established Gallery of Living Art. There and through his friends John Graham and Arshile Gorky, he became fascinated with Picasso, Braque, Miró, and other modern masters.

The mid 1930s were difficult financially for Browne. His work was exhibited in a number of shows, but sales were few. Relief came when Burgoyne Diller began championing abstraction within the WPA’s mural division. Browne completed abstract works for Studio D at radio station WNYC, the U.S. Passport Office in Rockefeller Center, the Chronic Disease Hospital, the Williamsburg Housing Project, and the 1939 World’s Fair. Although Browne destroyed his early academic work shortly after leaving the National Academy, he remained steadfast in his commitment to the value of tradition, and especially to the work of Ingres. Browne believed, with his friend Gorky, that every artist has to have tradition. Without tradition art is no good. Having a tradition enables you to tackle new problems with authority, with solid footing.”

Browne’s stylistic excursions took many paths during the 1930s. His WNYC mural reflects the hard-edged Neo-plastic ideas of Diller, although a rougher Expressionism better suited his fascination for the primitive, mythical, and organic. A signer, with Harari and others, of the 1937 Art Front letter, which insisted that abstract art forms “are not separated from life,” Browne admitted nature to his art—whether as an abstracted still life, a fully nonobjective canvas built from colors seen in nature, or in portraits and figure drawings executed with immaculate, Ingres-like finesse. He advocated nature as the foundation for all art and had little use for the spiritual and mystical arguments promoted by Hilla Rebay at the Guggenheim Collection: “When I hear the words non-objective, intra-subjective, avant-garde and such trivialities, I run. There is only visible nature, visible to the eye or, visible by mechanical means, the telescope, microscope, etc.”

Increasingly in the 1940s, Browne adopted an energetic, gestural style. Painterly brushstrokes and roughly textured surfaces amplified the primordial undercurrents posed by his symbolic and mythical themes.

In 1945, Browne showed with Adolph Gottlieb, William Baziotes, David Hare, Hans Hofmann, Carl Holty, Romare Bearden, and Robert Motherwell at the newly opened Samuel Kootz Gallery. The Kootz Gallery was one of the premier art galleries in mid-century New York. Started by art dealer Samuel Kootz in 1944, it not only helped finance the works of emerging artists like Motherwell and Baziotes in the late 1940s, but it also offered the first post-World War II retrospective of Picasso in 1947. Kootz had a finely-tuned eye for great Abstract Expressionist artwork: when Jackson Pollock rose to fame in the late 1940s with his signature “drips,” Kootz reminded the public that Hans Hofmann was producing “drip” paintings as far back as 1940. With prior experience as an advertising executive, Kootz was also a relentless promoter for his gallery’s exhibits, trying to appeal to as wide an audience as possible. Kootz attempted to imbue his gallery’s shows with a sense of grandeur, as if each one was a true cultural event. In 1947, the first ever Picasso exhibition in the U.S. following the end of World War II took place at the Kootz Gallery. For a time, Kootz was Picasso’s exclusive representative and dealer in the U.S. When Kootz suspended business for a year in 1948, Browne began showing at Grand Central Galleries. In 1950, he joined the faculty of the Art Students League, and in 1959 he began teaching advanced painting at New York University.

Browne’s paintings are in many private and public collections including:

Arizona State University Art Museum

Boca Raton Museum of Art

Butler Institute of American Art

Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh/Carnegie Institute

Chrysler Museum of Art

Dallas Museum of Art

Everson Museum Of Art

Fogg Art Museum: Harvard University Art Museums

Frederick R Weisman Art Museum

Georgia Museum of Art

Herbert F Johnson Museum of Art

High Museum of Art

Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden

Joe & Emily Lowe Art Center

Kresge Art Museum

Memorial Art Gallery

Milwaukee Art Museum

Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts

Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute

National Museum of American Art-Smithsonian

Neuberger Museum of Art

New Jersey State Museum

Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts

Roswell Museum and Art Center

Staten Island Museum

The Brooklyn Museum of Art

The Canton Museum of Art

The Columbus Museum of Art, Georgia

The Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art

The Hudson River Museum

The Newark Museum

The University of Arizona Museum of Art

The University of Michigan Museum of Art

Ulrich Museum of Art